I’ve taught a version of Introduction to Russian Culture many times over the past several decades. I learned the basic material from Michael Flier at UCLA, then adapted quite a bit over the years, using music, religion, language, literature, geography, architecture, art, and a lot of history. The history has always seemed essential since many of the students who take the class (often to fulfill a requirement) don’t know much beyond the current headlines and a few key events.

So I’ve tended to start the first few weeks of class with an overview and a single volume history that goes pretty much from the origins of recorded history to the present. Generally, in such a book there are two hundred pages or so devoted to the time from about the 9th century to about the beginning of the 20th century, then another two hundred pages or so from the 20th century to the present. But we’ve generally had a second class that covers more contemporary material, more or less from World War II to the present, which means we really only need the first two hundred or so pages of the book. I have gone back and forth over the years between having students read the whole thing, even though we won’t really do much beyond WWII in this particular class, or reading only up to the point where we’re going to be digging in. I’m still not sure which is better.

I thought of this today when a friend sent me a funny meme with a painting of Jesus just after his birth, being held by one of the wise men, and in the background is a tiny crucifix hanging on a wall in the nearby stables. In the meme, someone has circled the crucifix with a marker and written “spoiler alert!”

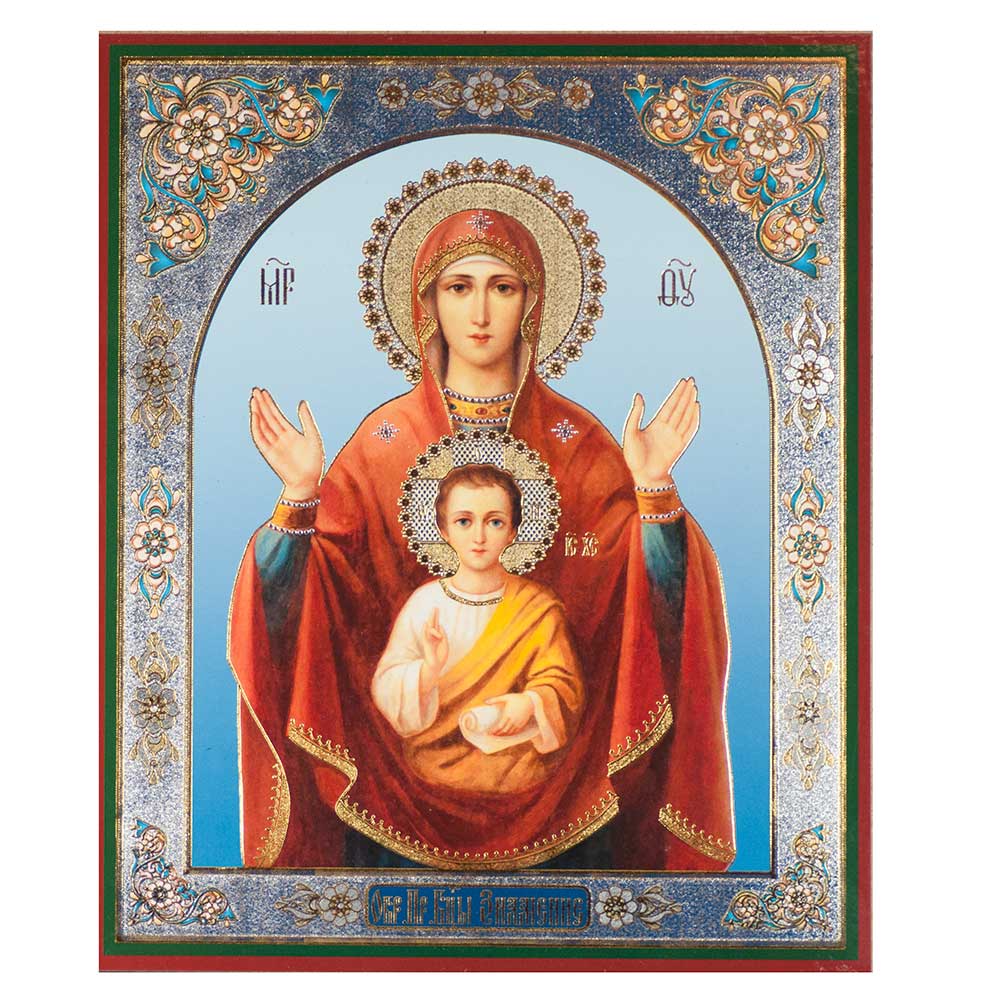

It is a funny meme, but it also made me think of teaching the simultaneity of icon time in this class, where a figure like Mary might appear in a characteristic pose, her hands outstretched, her palms facing forward (which art historians call the “Virgin orans”) and then, pictured in her midsection, almost as if inside her womb, is Jesus. But Jesus is not shown as a baby typically. Instead, he is often shown as a young man, fully robed, one hand extended.

I once asked a specialist at the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg about this, and she suggested I try not to look at such depictions through a secular perspective. The things depicted might look like they should happen at different times (being inside or outside of a womb, for instance, or being an adult or a child), but that is only from a human perspective. The world depicted does not have time like that. Everything in the world of the icon is, in effect, simultaneous. This is the time perspective of the icon. This kind of challenge to our usual ways of thinking and interacting with the world is also one of the reasons why I love teaching this material to students.

The irony of my struggle over how much history — which is the unfolding of human events over time — to include in such a class versus the eternal perspective of the icon, where such unfolding is understood as secondary and fundamentally limited, is not lost on me. This irony has helped me to think about where to focus more than once, and not just in this class.