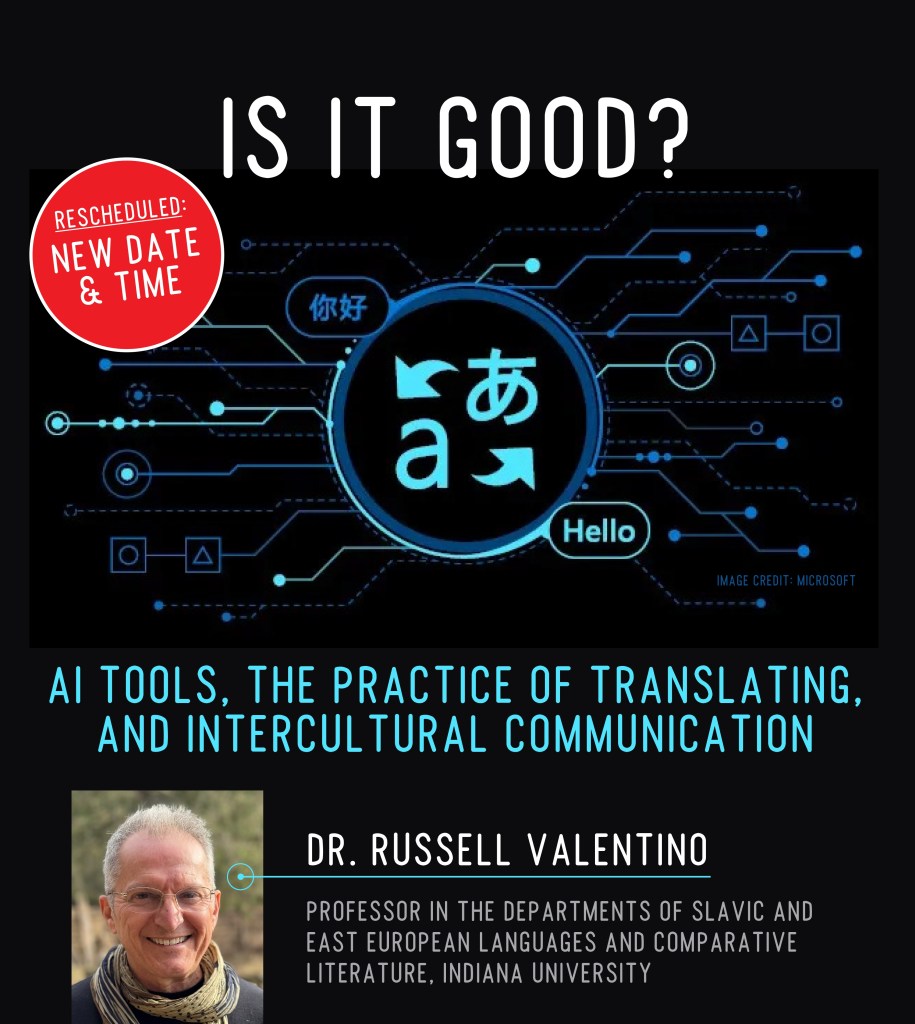

I’ve been thinking through the stimulating couple of days I got to spend at the invitation of Kristin Dykstra at St. Michael’s College (SMC) last week. The subject of my talk, and the reason for my visit, was AI and translation. The presentation, entitled “Is It Good? AI Tools, The Practice of Translating, and Inter-cultural Communication,” was part of a year-long first-year seminar, so the forty or so attendees were bright first-year students thinking hard about something that we’re all trying to figure out.

My still evolving thoughts were a continuation of and expansion upon two presentations from the past approximately six months, both on similar topics, first at the annual conference of the International Association of Teachers of Esperanto, the other at Princeton University’s Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication in September, 2025. I am extremely grateful for these opportunities, which are helping me to hone my thinking and approach to the topic.

As the SMC event was primarily for students, Kristin followed up with a series of points for classroom discussions that followed. I wish I could have been there to take part. I got Kristin’s permission to post the excellent summary below.

There’s so much more to say, of course, but it’s a start.

TAKEAWAYS FOR UNDERGRADUATES: Russell Valentino on AI [summary by Kristin Dykstra]

Dr. Valentino approved these summaries as a way to frame his talk.

Premise: We do still need to train students in language skills and cultural contexts, despite the emergence of new AI tools.

Why:

- You will need that experience and competency, in order to fact-check evolving and imperfect AI tools.

- As experienced translators like Dr. Valentino are seeing, the work we call “translation” becomes very different when you redirect human work into work with AI prompts and MTPE (Machine Translation Post Editing) processes.

Essential observations as of 2026:

- AI tools are systematically prone to errors and bias, as well as “bullshit” (hallucinations: non-truths produced by tools that lack the capacity to evaluate truth)

- Professionals need to be able to recognize and correct these problems, as a habit and a practice. This is especially true for high-stakes situations. But even in situations that seem more routine, this habit can have important results.

- Fact-checking is therefore a key best practice.

- These realities reduce the “efficiency” that marketing often emphasizes, esp. as companies sell AI tools.

- Humans are not disposable in the process.

- Education is not disposable in the process.

Working with AI Tools redirects your attention to interaction with those machine tools, instead of humans and human expression.

- There can be value in using machine tools. We should be aware that this value will often be different than the value we get from interacting with humans, and we should think of tools as complementary, not a replacement for persons.

When too much of our work becomes focused on tools – on writing prompts for them – here are some valuable aspects of translation that get compromised.

- Human interaction, and with it, a grasp of the constantly evolving experience and complex social contexts, factors with which machines notoriously struggle.

- Benefit to the translator, as a human who learns from this engagement, and grows professionally and personally as a result.

- Innovation: Unexpected discoveries. If too much is pre-planned, in order to fit a machine tool procedure, the human using the tool is continuously directed back to the existing procedure demanded by the tool. This is inherently conservative, therefore limiting.

There is still a lot of work to be done to get to a place where AI tools represent real “accuracy” on the job, or true “efficiency.” Tools should not stifle traditional benefits of cross-cultural experience: human innovation, professional growth, psychological growth, and perhaps most of all, emotional growth.

Is it good? Dr. Valentino concludes that in order for us to build the judgment or discernment to decide answers to this question, we have to go through the real, bodily process of translation and interpretation. It is much like being a musician or athlete: talking about the activity does not give the same growth or learning as actually doing it, habitually, over time.

###